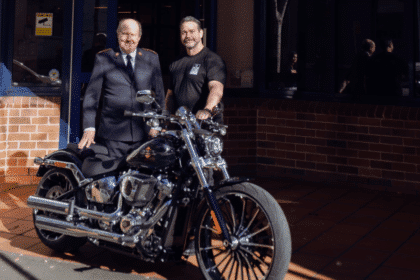

Byron Sharp allegedly ‘skewers’ Binet & Field’s 60/40 rule, and ‘backhands’ Mark Ritson – but rather than polarised viewpoints, embracing the value and nuance of relative experience and expertise would be more progressive for marketing thinking, argues B&T’s regular columnist Dan Machen (pictured below).

With a keynote that was reportedly a broadside to the Godfathers of Binet, Field & Ritson, Byron Sharp has once again been portrayed, as the Holy Ghost of Marketing – a kind of omni-reply guy for marketing thought leadership. If the headline has added GST then that’s one thing, cocking a snook at practitioners as diligent and learned as Peter Field and Les Binet, or as experienced as Mark Ritson, is not a great look. As ever, our thought leadership retrenches to a click-swinging contest, when beneath the headline grabbing polarisation we are trampling nuance that actually has value to advance collective thinking. To address some of the points specifically lifted from the article in the bullets/shots fired below:

- Professor Byron Sharp told marketers to concentrate on the basics – building mental and physical availability and advertising consistently throughout the year – to drive growth.

- Addressing the divide between brand and performance camps, or “activation and advertising”, Sharp said brands need both, but that without building memory structures through advertising, no amount of performance advertising would deliver growth.

- Sharp dismissed the 60:40 brand to performance ratios formulated by Les Binet and Peter Field as based on unsound awards data.

I don’t doubt this was both accurately and gleefully reported – a seeming stoush like this among marketing’s literati makes for great headline fodder. My issue with it is that, amidst these generous broadsides and backhanders, it ignores what diligent practitioners like Binet and Field have already conceded in terms of limitations in their dataset and rides roughshod over the nuance they themselves have subsequently added to their body of work.

In ‘dismissing’ mnemonics like 60/40, which raises the focus on the balance of brand advertising versus performance activation, we devalue a debate that was progressive, for a suggested schism that isn’t as dramatic as the headlines would have us believe.

To address the points raised, Binet and Field’s work aligns to quite a significant degree with Byron Sharp as per this quote from Les Binet, “The most effective marketing strategies talk to everybody. Marketing is a numbers game. Or, as Byron Sharp from world-renowned Ehrenberg-Bass Institute has proved repeatedly, to grow your brand you have to reach both buyers and non-buyers. It can’t be said enough.”

Building on Binet, Field and Ritson’s work, they all champion a need for what Ritson calls a need for ‘Bothism’ – championing the top of funnel and bottom of funnel and focusing increasing on optimising the mix for effectiveness. Binet and Field specifically assert brands relying on performance activation alone are likely to suffer sub-optimal growth and speak to the need for balance – at pains to point out the particularly caustic effect of turning off brand advertising has on reducing effectiveness and limiting growth.

In Binet and Field’s subsequent, ‘Effectiveness in Context’ paper, they double down on brand advertising’s effectiveness, saying,“there is no context in which short-term sales activation is the primary driver of growth.” Furthermore, as per the title Binet & Field specifically pull at their own 60/40 principle, highlighting that “overall, brand spends need to increase, but there are significant variations by sector”. This flexes by category, brand/product life-cycle, degree of innovation and also the predominant channels brands operate in.

Based on all of the above the protagonists in this particular fight to my mind seem to agree violently, more than anything else.

Importantly, Binet and Field also recognise the limitations in their dataset, but to label it ‘awards data’ is so reductive as to come across facetious. The IPA databank has more than 20 years’ data, it’s looking at the commercial outcomes of winners and non-winners. It’s analysis is a diligent attempt to move Marketing thinking forward and while not perfect is a stride in a direction that is additive to the endeavours or many – especially on the focus on new customers and as brand advertising as the primary lever of growth.

In terms of what Sharp goes on to say, there is real merit in his focus on sophisticated mass marketing and finding what’s heterogenous about the largest audience opportunity versus niche targeting and he gets a real AMEN in criticising the lack of frequency cap on ad repetition of ads in the same BVOD break.

Two elements Sharp repeatedly raises that are worthy of debate, however, are his assertion that for mental availability, “you have to reach everyone in the category, you can’t just target the susceptible … and spread your budget across time slots, across locations.”

If you are Mars or Coca-Cola you can probably hit 90 per cent of all adults at a +6 frequency. The challenge for so many brands is that the blitzscale approach feels cost-prohibitive. (Appreciate the challenge is make your budget go as far as possible, but the inaccessibility of reaching all buyers is an elephant in the Zoom that doesn’t often get talked through.)

The second point, that dynamic creative undermines the ability to create memory structures through consistent use of distinctive brand assets. I think in the media context in which this remark is mainly made the comment is largely valid. However, again resisting black and white inflexible truths is that flexing brand codes once established can be a great way to create a cognitive close for an audience and actually provoke recall as they create new associations and inject fun. More owning a more cognitive entry point that the typical category entry points beloved by Ehrenberg-Bass.

As opposed to pistols at dawn saying ‘your data be damned!’, my passionate plea to Marketing thought leadership is to be a little less, dare I say it, Byronic. Embrace the arguments put forward by Binet & Field and Ritson as the positive steps that they were and are based on evidence-based findings and that invaluable additional data point in life – experience. Let’s be a little less binary in our exchanges and embrace a respectful dash of Bothism – as Mark Ritson said when he introduced the concept – “From now on, when presented with any marketing concept as superior to another, don’t reject that argument but try, mightily, to add the alternative view as well.”