This is the final part of a three-part series examining how digital advertising can fund disinformation. The first discussed the scale of the issue, the second sought to find out why the problem persists and efforts to stop the pain. This third and final part will delve into why this is such a serious issue and why the problem, though not new, matters more than ever.

“Follow the money,” said Imran Masood, DoubleVerify’s country manager AUNZ, “Wherever there is an opportunity for a scammer to come in and scam somebody… they’re going to try and do it.”

But following the money in programmatic advertising is not easy. For example, adtech platforms allow publishers to hide their identity, making who they are unclear to advertisers. What’s more, adtech platforms even allow publishers to buy ads and resell them to other sites.

Tracking the flow of money is so difficult that around three per cent of all ad spend goes completely unaccounted for — and remember, this is an industry valued at many hundreds of billions of US dollars — and it is impossible to match more than two-fifths of transactions from end-to-end.

But, while there is a clear issue around accountability for programmatic advertising, there is an even greater issue around the truth. Who gets to decide what is safe for brands to advertise next to and who gets to decide what constitutes misinformation during a time when news moves so quickly and public figures are able to speak directly to their audiences?

Reselling A Nightmare

“We’re not saying ‘no resellers,’ but the suggestion is that since ads.txt helps legitimate value-add sellers, publishers should do their part in due diligence evaluation. Demand Side Platforms tend to be more suspicious about second-level reselling,” wrote Sam Tingleff in 2019 then chief technology officer of the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) Tech Lab.

That situation has not changed since 2019, though a Google spokesperson told B&T that the firm has “strict… publisher policies that govern the types of ads and advertisers we allow on our platform and content we allow to monetise.”

However, it is quite easy to work out that some sites fall through the cracks.

Right-wing news site Breitbart still lists 32 Google-affiliated listings on its ads.txt page. Rumble.com has three. It hosts the likes of Dinesh D’Souza, whose film 2000 Mules falsely alleges that Democrat-aligned individuals rigged the 2020 US Presidential election, and Dan Bongino, who The New York Times listed in its top five 2020 election “misinformation spreaders.”

Even Fox News, which settled its defamation suit with Dominion Voting Machines for a record AU$1.1 billion has Google records in its ads.txt file. Of these, Fox News has two reseller listings, Rumble has one and Breitbart has a whopping 24.

As Integral Ad Science’s Jess Miles told B&T last time, it is unlikely that big brands are funding these sites as their brand value is too important to them. Rather, it’s the smaller advertisers inadvertently sending money to sites that spread disinformation as they simply don’t have the tools or the finances to make it happen.

But, by allowing resellers and allowing publisher accounts to be confidential, adtech platforms are prolonging a problem and reaping the financial benefits.

For Lisa Given, professor of information sciences and director of social change at RMIT University, the businesses at the heart of programmatic advertising can and should be doing more to stop the funding of misinformation.

“I think they can and many of them are trying because consumers and businesses are demanding that of them. But it’s a question of scale and how successful they’re going to be particularly when they’re having to weigh out the loss of business revenue, the staffing and technology required to chase these aspects,” she explained.

“It’s not just the large companies like Google trying to attack this on the one side but you also have major players on the other side that have a real vested interest in promoting disinformation. The scale of that can be quite significant as well. It’s not quite as simple as Google trying to battle one or two small players. They could be battling big money corporations.”

Funding A Polarised World

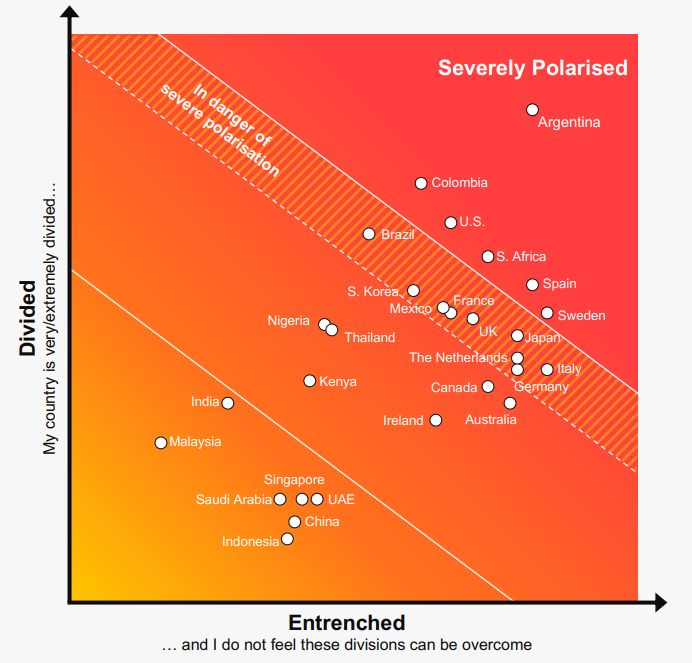

It’s a truism to say that the world is more divided than ever. But there are some statistics to prove it.

Edelman’s Trust Barometer report found that 45 per cent of Australians believe that the country is more divided than ever. In fact, 48 per cent of Aussies say that the media is a source of misleading or false information. Just 37 per cent felt that the media was trustworthy at all.

In fact, Edelman found that no news source is trusted in Australia in 2023. Traditional media was only trusted by half of Australians (up two points compared to 2022), owned media by 31 per cent (down two points), and social media by 25 per cent (down one point).

It would be incorrect to say that digital advertising and the sweeping changes to the business models and viability of news media organisations brought on by digital advertising caused this distrust in the media. Certainly, it has exacerbated that mistrust but, as we have established before, the general public has, to some degree, always held a level of scepticism over the words they read in the press.

However, digital advertising has certainly made publishing mistruths to be significantly more viable and profitable for unscrupulous journalists.

But three-quarters of Australians said that they trusted their employers to “do what is right.” CEOs are also expected to publicly take a stand on the treatment of employees (91 per cent), climate change (78 per cent), discrimination (75 per cent), the wealth gap (74 per cent) and immigration (66 per cent).

In this context, it immediately becomes clear that while citizens might not trust the news they read, they trust the brands that they see. And, as advertising 101 courses will tell you, when a consumer sees a brand they like alongside a piece of content, they will be more likely to trust that content and vice versa.

Currently, the ad world is talking a lot about “purpose” and advertisers’ and agencies’ moral and financial obligations to do the right thing.

Andrew North, creative director at Icon Agency recently wrote in B&T that one of the joys of working in advertising (aside from the mounds of free arancini at events) is being able to “enact real and active change.”

“There is something wonderful to be said about doing work that creates real, positive change,” he continued.

“Commerce and purpose are not mutually exclusive. There is nothing inherently evil about success. It’s the way that one achieves that success, and the outcomes it creates that makes the distinction.”

But when great creative and media work can be undone through an opaque programmatic landscape that hides the sites that receive ads from the people selling them, it seems as though, while not mutually exclusive, commerce and purpose do not always make for good bedfellows.

However, one big question remains. Who gets to be the arbiter of truth in the multipolar fragmented world in which we live?

At What Cost Truth?

“It is quite interesting, isn’t it? People on the right calling out people on the left and saying ‘that’s a conspiracy!’ but that’s just another technique they have in order to keep that negativity rolling and to keep their message at the front of people’s minds,” said Given.

The divide between the left and right of the political spectrum seems to be growing wider. B&T, for example, has covered the Bud Light transgender influencer debacle at length.

To many, especially within the notedly urban and (seemingly) progressive advertising industry, the idea of a brewer tapping a transgender woman to be a spokesperson is laudable. However, for many others, the notion is laughable.

In fact, Robert Thomson, CEO of News Corp, reportedly told the International News Media Association (INMA) World Congress that he discovered a large company had an ad-buying ban on the New York Post.

“I asked the chief executive of one of the world’s largest companies why he had an ad ban against the New York Post,” he said.

“The chief exec said he was completely unaware of any such ban — so he checked, and to his genuine and annoyed surprise, a hyper-politicised agency flunkey had a Post prohibition.

“The medium may be the message but unless we are more assertive and there is more transparency, certain advertising agencies will indulge their worst instincts, ad nauseam.

He also said that the people behind the Global Disinformation Index were “arrogant armchair amateurs” and had “undue influence on ad spend by agencies and companies.”

The Post is a tabloid whose typical articles range from celebrity tittle-tattle to fear-mongering stories about Chinese militarism. It does do some good journalism but one should not confuse it for the similarly named New York Times or the Washington Post.

This divide extends beyond identity politics, as well. The election of Donald Trump to the US presidency and the Brexit referendum in the UK both demonstrated that, in the face of the repeated bleating of falsehoods, maintaining the truth is hard and that people will simply believe what they want to.

The same happened with the COVID pandemic and is happening again with the war in Ukraine. Many, falsely believe that the war is a complete hoax despite it extending for more than a year and racking up more than 100,000 casualties.

Closer to home, the Voice to Parliament referendum was always going to attract consternation. Accusations of misinformation around the referendum have been flying from both sides of the political aisle.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said opposition leader Peter Dutton had been amplifying falsehoods in the run-up to the vote.

“It is disappointing but not surprising that the loudest campaigners for a no vote have already been reduced to relying on things that are plainly untrue,” Albanese told parliament during a debate on the referendum.

“In his desperation, the leader of the opposition is now seeking to amplify this misinformation – and all of its catastrophising and contradictions.”

Dutton said that the voice would have “an Orwellian effect where all Australians are equal, but some Australians are more equal than others” and that it was “a symptom of the madness of identity politics.”

“The great progress of the 20th century’s civil rights movement was the push to eradicate difference – to judge each other on the content of our character, not the colour of our skin,” he said. “This voice, as proposed by the prime minister, promotes difference.”

Meanwhile, senator and leader of the One Nation party and Pauline Hanson, claimed that she had seen a letter penned by the National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) group listing the details of the voice.

In particular, she claimed that the NIAA’s plan for the voice would lead to “Aborigines paying only 50 per cent the rate of income tax” and that “Aboriginal groups” would own the “beaches and national parks, and charging the rest of us to use them.”

The NIAA denied having written it, while a spokesperson for the Hanson said she had never actually seen the original. Unperturbed, Hanson later doubled down on the claims in Parliament.

“I remember being told when I came into journalism, ‘It is important to be first, it is more important first to be right.’ And I’ve seen so much of that change over my time because of technology and because of attitudes” said former ABC journalist Stan Grant at Cannes in Cairns.

“I don’t think there is anything in the media that is contributing to that better society. We are better off to turn it off… Yes, it is important to be informed. Yes, it is important to make good judgements in a democracy for the better of our society. Yes, it is important to know what is going on. But so much of what passes for news discussion or coverage is not about being informed, it is simply about the noise.”

And herein lies the problem. With such a febrile, fast-paced media landscape of which programmatic digital advertising is a cause, symptom and propagator, truth, context and informed debate are no longer valued socially or financially. There has to be a better way forward.