In this op-ed, Leif Stromnes, managing director, strategy and growth, DDB Australia, outlines the evolutionary concept known as reciprocity, by which all humans feel indebted to help one another or return favours due to social rules and shows why this knowledge should be considered by marketers. He warns, though, that it must be used subtly and skillfully.

In his famous book on evolutionary biology, Richard Dawkins describes the characteristics of the “Selfish Gene,” the immutable force that ensures the traits that aid the individual’s survival and reproductive success will be selected and passed down to its offspring.

According to this definition, the evolution of altruistic behaviour, where one animal aids the fitness of another animal to their own detriment, seems highly impractical. It’s also contrary to the survival of the fittest espoused by Charles Darwin and built upon by Dawkins.

Despite this obvious kink in the theory of evolution, there are many examples of altruistic reciprocation in nature: cleaner fish who are not eaten when they swim amongst the teeth of their hosts, birds issuing general warning calls at the approach of predators and perhaps the most altruistic act of all, primates cleaning and preening each other to control ticks, fleas and other parasites.

This anomaly was settled by Robert Trivers in 1971, whereby through advanced computer modelling, he proved that the practice of reciprocal altruism is stable in an evolutionary sense because natural selection prioritises individuals who return the altruistic favour. This was most apparent amongst species when there was a high degree of mutual dependence. This makes sense because mutual dependence implies that species do better when they cooperate, and this often forces individuals to stay together in groups. These groups rely on each other for basic survival and therefore increase the chances of altruistic acts being reciprocated.

Humans are the most socially adapted creatures on the planet and our success as a species is largely due to our ability to work collaboratively in groups. It follows, then, that we have an acutely developed reciprocation bias. We derive a significant competitive advantage from reciprocity because it means that a person could give something (for example, food or care) to another with confidence that the gift was not being lost. As a consequence, we make sure our members are trained to comply with the reciprocity rule. Each of us has been taught to live up to the rule from childhood, and each of us has felt the social sanction and derision that is applied to anyone who violates it. It may well be that a developed sense of indebtedness flowing from the rule of reciprocation is not only a unique property of human evolution but of culture, too.

It’s no wonder, then, that savvy marketers have long understood that the psychological power of reciprocity is one of the most potent levers for gaining compliance amongst potential customers.

What makes reciprocity so successful as a marketing tool is its pervasiveness amongst all populations and its potency in exchanges of every kind.

Additionally, reciprocity has unique qualities that make it particularly useful and profitable.

One of these reciprocation qualities is the fact that the receiver does not have to ask for a gift or favour, to feel indebted. This is useful for marketing tactics like sampling, whereby a customer passively accepts a free sample and then immediately feels psychologically obligated to make a purchase. One of the most stunning examples of this tactic in action was documented by Vance Packard in his classic book The Hidden Persuaders. In the example, an Indiana supermarket operator sold an astounding 450 kilograms of cheese in a few hours by putting out the cheese and inviting customers to cut off slivers for themselves as free samples.

Another useful feature of reciprocity is the imbalance of favour and return favour. In other words, there is no requirement for it to be like for like. This favours marketers once again in that a relatively modest outlay can result in a far larger return. This tactic works well in charity appeals. In the United Kingdom in 2013, researchers working with fundraisers approached investment bankers as they came to work and asked for a large charitable donation – a full day’s salary, amounting to over $1,000 in some instances. Remarkably, if the request was preceded by a gift of a packet of sweets, contributions more than doubled.

Some simple tricks can be applied to make reciprocity work even harder. Personalising the gift has been shown to increase returns four-fold, and customising the gift to the person’s current needs is another way to not only ensure compliance but to increase the size of the reciprocated favour or payment.

Whilst reciprocity is one of the most powerful tools in the marketer’s toolbox, caution needs to be exercised. Executed subtly and skillfully, it pulls on the emotional heartstrings in a way that few other marketing tactics can. But in an evolutionary quirk, our awareness of the “cheater” gene where people use reciprocity to create advantage for themselves through trickery is extremely well adapted. Over millennia, humans have developed a keen sense for being taken advantage of, and under these conditions, reciprocity not only falls flat, it creates negative feelings of mistrust, leading to rejection of the reciprocated offer and, in extreme cases, derision too.

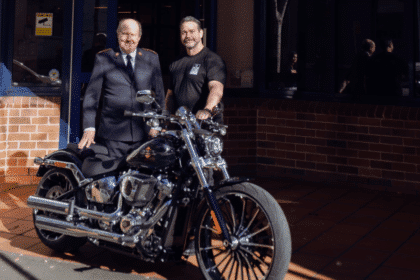

This brings us full circle to the title of this story: Why doctors no longer receive gifts from pharmaceutical reps. The practice has been banned in Australia because the power of expertly executed reciprocity has proven to be so strong that even smart, mature, sophisticated men and women in the medical profession have little rational defence against its emotional appeal.