Who’d run a grocery store in Australia? Currently, Woolworths and Coles are facing not one, not two, but five separate inquiries into their pricing practices at both state and federal levels and from the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC).

From a consumer’s perspective, the math seems simple. In 2022, Coles and Woolies controlled nearly two-thirds of Australia’s grocery market with ALDI a distant third with a nine per cent share. This kind of power makes Coles and Woolies unavoidable for consumers but it also makes them seem irrepressible in their quests for profits — while that may not actually be the case at all. Of course, both retailers protest that they are not in the business of squeezing Australians until the pips squeak.

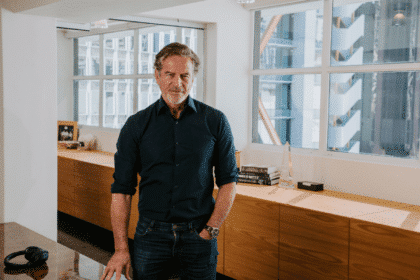

Andrew Hicks, Woolworths’ longstanding chief marketing officer, told B&T that “It’s become ‘we can help you spend less at Woolworths’. It’s about saying to the customers we care about and actively want to help you.

“The customer notices what you do, not what you say. It’s about actions — big and small — and small actions matter,” he added.

Amanda McVay, the relatively new CMO of Coles, meanwhile told B&T that she was determined to help “Australians eat and live better” and was focused on “delivering for communities.”

In their submissions to the Senate Select Committee on Supermarket Prices, however, both firms stressed that it was down to the complexity of the food market in Australia. Around 70 per cent of Australian livestock is exported, rather than sent to Aussie retailers, for example, and the global interconnectedness of foodstuffs has led to wholesale price rises and, simply, the weather. In effect, both brands seemed to suggest that they were doing everything they could to make lives better for Australians despite the hands tied behind their back. They were also quick to highlight that they recorded significantly lower profit margins than other retailers.

“The price of fruit and vegetables in Australia is primarily driven by supply and demand,” said Woolies in its submission.

“For example, in 2022, prices went up when heavy rain and low sunlight associated with La Niña reduced the available volume of fruit and vegetables on the market. Better growing conditions in 2023 improved availability, and fruit and vegetable prices have been in deflation since the middle of 2023.”

The grocer added that it sourced around 96 per cent of its fresh fruit and veg from Australian growers and that “almost all” of its submit pricing quotes every week.

Coles, meanwhile, took a stab at the highly politicised price of red meat. It said that the overwhelming majority of its red meat came directly from farmers at prices agreed with them.

“These contracts provide security of demand for our suppliers and security of supply for Coles and our customers. While livestock prices fluctuate, there are many other operational costs that impact the price consumers pay. Those costs, including transport, processing, packaging, labour and operating costs such as for refrigeration and energy, have gone up and remain high,” it said.

But does any of this matter to consumers? And, perhaps more importantly, does any of it pass the pub test? Nitika Garg, professor of marketing at UNSW, said that it all depends on just how deep the varying inquiries delve into the matters — or whether the legislators use them as a chance for some political grandstanding.

“Is [the inquiry] going to give some conclusions on the issues or will the government implement some changes that would overhaul the industry?” she told B&T.

“If they are found guilty of price gouging, I think it is more of a regulatory issue that has allowed this to happen. It would then fall on the government to correct the supply chain issues along the way.

“I don’t think people understand the complete details of how the market works. If you tell them there has been a drought and this has impacted our supply chains for bananas in Queensland and the price goes up, they’ll broadly understand why this has happened. But most people do not have the time or expertise or are willing to understand the market. So, even if the inquiry finds that they couldn’t have done anything more or much different, people aren’t going to change their perception.”

However, she also pointed to the price of milk. Coles, for instance, introduced a $1 litre of milk in 2011, which now sells for between $1.50-$1.60 per litre. In June 2022, the price jumped by 25 cents. The retailer said that the price increases were “due to ongoing cost increases in the supply chain.”

“The prices went up drastically because of the crisis. This was a big shock to consumers but even after the crisis was resolved, the prices did not come down. They were like ‘Oh well, consumers are used to paying more now. So why should we bring the prices down?'”

Woolworths is due to release its half-year results for its 2024 Financial Year next Wednesday. Coles is set to release its results for the same period on 27 February. There is no reason to expect that the retailers will not announce huge profits — despite their protestations that their profit margins sit at only 2.6 per cent, compared to Wesfarmers 6.5 per cent, JB HiFi’s 5.3 per cent and Harvey Norman’s 13.8 per cent.

High-ranking execs are due to appear in front of the respective inquiries soon. Woolies’ CEO Brad Banducci will be speaking to the Senate Inquiry, as well.

There is one beneficiary to this whole episode, though — ALDI.

“It’s a tough environment at the moment, and what happens in times like this is that consumers are willing to try an alternative, which is where we come in,” ALDI CMO Jenny Melhuish told B&T.

“This is our chance to change perceptions, win them over, show them that shopping with ALDI is not a compromise, and although we offer the lowest prices, it is not at the expense of quality. We do not have all the frills, and for good reasons, which we are proud of.”

Is there any way around this? Garg believes that the best defence for Woolies and Coles’ brand reputation would be a good offence.

“I would have emphasised communications ahead of time. As soon as the prices were going or people were beginning to hurt, I would have ramped up the communication to help mitigate some of the backlash,” she said.