Thinking Of Sponsoring An Olympic Athlete? Don’t Bother Argues The Latest Research

In this opinion piece, Zac Anesbury (pictured below), a senior research associate at the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute based at the University of South Australia’s business school, takes a look at the sponsorship of Olympic athletes and asks is the (often) massive cost even worth the ROI…?

As the world is approaching the starting line for the Rio 2016 Olympic Games, so too are the sponsorship deals for athletes. However, with multiple brands often sponsoring the same athlete, can a brand ever really ‘own’ an athlete as a distinctive asset? The power of a distinctive asset is that when you see it, you think of the brand name. It creates another opportunity for the brand to be thought about by consumers.

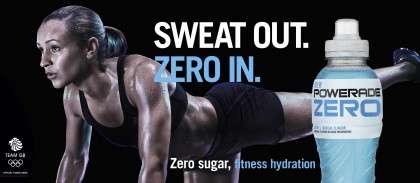

Looking back on the London 2012 Olympic Games, track and field star Jessica Ennis (now Ennis-Hill) was officially sponsored by Adidas, Olay and Powerade (just to name a few). Although none of these brands were direct competitors, they were all trying to create a link with Ennis. But, when people see Jessica Ennis, what brand name or names do they think of? Did any brands successfully build associations with Ennis?

The Ehrenberg-Bass Institute* surveyed the British public shortly after the London Games. A total of 770 people, aged from 16 to 89, completed our online questionnaire. Respondents were shown images of athletes, and asked to name up to four brands that came to mind. They had to recall the brands without prompting, which is a harder test that reflects a stronger link from the athlete to the brand in memory.

Our sample of athletes included Andy Murray, Bradley Wiggins, Chris Hoy, David Beckham, Jessica Ennis, Louise Smith, Mark Cavendish, Mo Farah, Oscar Pistorius, Usain Bolt and Victoria Pendleton.

Low levels of sponsorship association

Unfortunately, the news is not good for brands. Only 1.5 per cent of people linked the sponsoring brands to the athlete on average (yes, less than 2 per cent, and we showed participants pictures of the athletes). Having multiple sponsors creates two issues for brands. Firstly, seeing the athlete in ads for multiple brands makes it harder to establish memory links. Secondly, it means the different brands have to compete for retrieval in consumer’s minds when they see the athlete. I might see Usain Bolt and think Visa one time, then the next time Nissan and another time Puma. The more competitive the field of endorsing brands, the less likely any will gain major benefits from the endorsement.

It was a poor race, but there were front-runners. Visa was in the gold medal position, with 20 per cent linkage to the World’s Fastest Man – Usain Bolt. Coming home with silver was Sky, with a 10 per cent linkage to British cyclist Bradley Wiggins. There was a tie for bronze between David Beckham/Adidas and Jessica Ennis/Powerade.

Top brand for each athlete

| Athlete | Event | Brand | % |

| Usain Bolt | Sprinter | Visa | 20 |

| Bradley Wiggins | Road Cyclist | Sky | 10 |

| Jessica Ennis | Track & Field | Powerade | 6 |

| David Beckham | Football | Adidas | 6 |

| Andy Murray | Tennis | Adidas | 5 |

| Mo Farah | Runner | Adidas | 4 |

| Victoria Pendleton | Track Cyclist | Pantene | 4 |

| Mark Cavendish | Road Cyclist | Sky | 4 |

| Chris Hoy | Track Cyclist | Sky | 2 |

| Oscar Pistorius | Sprinter | BP | 1 |

| Louis Smith | Gymnast | Adidas | 1 |

| Average | 5.6 | ||

The fragmentation of brands for each celebrity

Because people were free to associate any brand with the athletes (up to four or none), the responses were very fragmented. Athletes were associated with about 19 different brands across respondents on average; this means any sponsor was competing with 18 other brands. David Beckham led the pack with 28 brands linked to him, including his own ‘brand Beckham’! Even Visa was competing against 19 other brands for Usain Bolt in its sprint to the finishing line. Such low linkage, makes it difficult for the endorsement to build brand equity.

A signal of where advertisers might be handicapping themselves is that consumers often mentioned general categories (e.g. a breakfast cereal, a sports drink) rather than brands. Marketing dollars fall short when viewers connect the category to the athlete, but not brand name.

But more damaging to the endorsing brand is when direct competitors pop into the consumers’ heads. Powerade, for example, was linked with long distance runner Mo Farah twice as often as his official sponsor Lucozade.

Tips for building brand linkage with an athlete/sports event

Here are some tips for leveraging the fame of an event or athlete and still achieving good results for the brand.

- Athlete selection – Pick an athlete that won’t feature in campaigns for multiple brands. There is a temptation to follow the crowd and go with big name athletes, but remember, if the focus is the event and the brand, using a lesser known athlete can help you leverage the event, but still spotlight the brand and its message. The athlete becomes part of the execution, not it’s focus. If the athlete is relatively unknown (and therefore uncompetitive) it will be easier to build up links to your brand.

- Fresh creative – Make sure your advertising creative style deviates from the standard cookie-cutter athlete themed ad. This will decrease the chance of the ad being linked to other brands (including direct competitors). The more your ad looks like the archetype, the greater the chance of misattribution.

- Prominent branding – Make sure the focus is on the brand, not just the athlete, to give the brand a fighting chance to attract attention. Strong branding is very important when other ads (shown at the same time) contain similar creative ingredients, such as including an athlete. Strong branding also helps to quickly link that fresh creative style to your brand, which penalizes any mimicking by competitors.

By branding strongly, deviating from the athlete-ad archetype and choosing athletes that will not be promoting multiple endorsements, you will help customers build links to your brand and get better value from your sponsorship.

Interested in sports marketing? Make sure you’re at The Ministry Of Sports Marketing conference in Sydney on 19th July 2016. Full details are available here.

* The Ehrenberg-Bass Institute, based at the University of South Australia Business School, is the world’s largest centre for research into marketing. For more information visit www.MarketingScience.info

Latest News

TV Ratings (18/04/2024): I’m A Celebrity Wins Prime Time And Key Demos

Aussie viewers can be a harsh lot at times. Only days after Ellie Cole bled her heart out, she has been sent packing.

Effie&co Launches New ConnectAsia Division To Help Aussie Brands Market To Asian Consumers Overseas & At Home

Not provided is advice on using chopsticks and not spilling ramen down your shirt.

Cashrewards Sets Out Stall For New CMO

Thinking of applying for the Cashrewards CMO gig? Here are some insider tips that, yes, are tantamount to cheating.

‘I Ask For The TV Industry To Stand Up And Defend Itself’ – Seven Boss James Warburton Steps Down

The Seven supremo heads for the exits after five years. Here's hoping the Spotlight team organised the farewell bash.

Poh! Jamie! Adriano! Paramount ANZ reveals its tasty plans for this year’s MasterChef

It's your fan's guide to this year's MasterChef! Although no tips on how to pronounce crudités or use a un fait-tout.

Dentsu’s iProspect Partners With MOOD Tea Ahead Of May Campaign Launch

We love a Mood Tea here at B&T. Although we do store old screws and nails in the International Roast caterer's tin.

Opinion: When Culture Starts Eating Itself: Navigating The Age Of Self-eating Nostalgia

Born boss David Coupland asks is adland going through a nostalgia period? But please, no repeats of Best Of Red Faces.

Who’s Going To Cannes?! The TikTok Young Lions Winners!

It's Aussie adland's next gen! They're off to Cannes with high hopes of bringing back a Lion & a foot-long Toblerone.

Adobe Launches Express Mobile App With Firefly AI

Want to be the coolest kid at Friday staff drinks but forgot your retro Nikes? This new Adobe wizardry may do the trick.

ThinkNewsBrands & IMAA Extend News Publishing Education In Brisbane

Industry duo takes its publishing roadshow to Brisbane. Was disappointed no male attendees were wearing walk socks.

B&T Chats With Wavemaker’s Provocative Pioneers On Their Cross-Pacific Sojourn

B&T TV heads to Wavemaker's Sydney digs to interview two staffers from its New York & LA digs. If that makes sense?

HoMie & Champion Launch “Give One. Get One” Campaign Supporting Youth Homelessness Via Town Square

Much like the fête's prized chutney wears a blue winners sash, so too should this top initiative from HoMie & Champion.

Thinkerbell Takes Us Back To Summer In Latest Work For XXXX

This beer ad wants to take you back to summer! Just minus any chance of a shark attack on your morning bus commute.

Cannes Lions Unveils 2024 Programme Featuring Queen Latifah, Jay Shetty & P&G’s Mark Pritchard

Are you one of the lucky ducks heading to Cannes in June? Check out the headliner acts you'll be queueing hours to see.

Scroll Media Recruits Costa Panagos From Twitch

Costa Panagos set to bring South American flair to the Scroll offices. Assuming that he is, indeed, South American.

Year13, Microsoft & KPMG Australia Launch AI Course For Gen Zs

Born around the 2000s? Need to amp up your AI creds? This guide's for you (although it's not really that age specific).

General Motors Snares Heath Walker From Scania

Do you rage about oversized American cars on our roads? You need to bail up Heath Walker at parties & industry events.

VML Launches New “Envoyage” Brand For Flight Centre

VML unveils new brand for travel operator Flight Centre. Alas, no sign of those paid actors pretending to be pilots.

Subaru Places Media Account Up For Review

Subaru puts media up for review, as adland journos get set for mandatory "agency drives off with..." headline.

TV Ratings (17/04/2024): Contestants Faced With Harsh Realities As Alone Australia Heats Up (Or Cools Down)

Alone still doing the business for SBS. Overly long train journeys not doing the business, but they persist anyway.

Ben Fordham Loses Number One Spot As Ray Hadley Celebrates 156th Ratings Win

The radio numbers are in! Discover who's off for a boozy lunch today & who's waiting for the dreaded HR death knock.

Gourmet Ice Cream Brand Connoisseur Launches New “Thrill Your Senses” Iteration, Via SICKDOGWOLFMAN

Rattling the old "truth in advertising" adage comes this ice-cream spot full of noticeably thin people.

Paramount’s Global Sales Boss: ‘Australia’s Converged Model Is A Blueprint For How I’d Like All Of Our Markets To Be’

Paramount's global sales boss gives local sales ops the thumbs up. Didn't weigh-in on the Lisa Wilkinson debacle.

TikTok Starts Testing Its Instagram Rival In Australia

In exciting news for piano playing cats & brattish pranks in shopping centres, TikTok unveils its Insta rival plans.

Man Wrongly Named By Seven As Bondi Killer Hires Lawyers

Struggling to save for a house deposit? Why not get wrongly identified by Sunrise!

Smartsheet Appoints Indie Agency Sandbox Media To Its Media Account

Can't stand your colleagues? Like to dob them in when they miss a deadline? These work management platforms are ideal.

Boss Not Letting You Come To Cannes In Cairns? Use This Business Case To Convince Them!

Stingy boss won't spring for a ticket to Cairns? Add this to your persuasive argument repertoire. Or grovel.

Alt/shift/ Brisbane Builds Portfolio With Ausbuild Creative, PR, Content & Social Account Win

The Brisbane comms/PR agency lands constructor Ausbuild. Also hoping for a discount on its new glass conservatory.

Young Guns Versus The Old Guard: Who Adds More Value to Our Industry?

Cannes In Cairns poking this hornet's nest in a lively debate. Just so long as the oldies can get up the stairs.

70% Of Aussies Don’t Have Green Power Plans ENGIE Says In Major Brand Campaign Via HERO

Are you the notorious "light leaver on-er" in your flatshare? Quell any infighting with this green energy news.

PrettyGood Launches Offering Brand & Media Solutions For Australasian SMEs

B&T applauds the charitable nature of this new agency. Although we'd hate to see it impact any Chrissie present sends.

A Blunt End: Dolphins Medicinal Cannabis Sponsorship At Risk

Yes, it's another NRL drug story. Yet, thankfully it doesn't involve coke in Kuta during the off-season.

Slew Of New Creative Hires At Leo Burnett Australia

Ahhh, all black! The outfit of choice for agency creatives, David Jones staff and everyone in Melbourne.

Under Armour Unveils Local “Live in UA” Campaign

American apparel brand set for yet another tilt at the Aussie market, as Nike declares "we'll see about that".

Pepsi Launches New Look, Refreshing Classic Fashion Staples Via Special PR

Are you always the bridesmaid, never the bride, as the old saying goes? How do you think Pepsi feels?

Pure Blonde Returns To A Place Purer Than Yours In New Campaign Via The Monkeys

B&T's always been a huge fan of the 'drink yourself thinner' diet plan. So big thanks to Pure blonde, vodka & tequila.