How To Swear In Your Farking Ads

In this guest post, Edge’s executive creative director Matt Batten (pictured below) takes on the rather fruity topic of how to swear in ads. And, yes, the article contains its fair share of swearing! You have been warned…

“Daddy, when are you going to teach me how to cut with a sharp knife and use naughty words?” asked my five-year-old as I drove her to daycare.

I figure she’ll be dropping f-bombs long before our client brands will.

But why? After all, they’re just words. And yet, they’re not ‘just’ words.

There are currently 171,476 words in the English language. Of those, the Collins English Dictionary determined there are just 16 truly naughty words, after downgrading 54 others from “taboo” to “slang” or merely “informal”, including bollocks and gangbang.

Over the centuries, taboo words have changed. A medieval nun wouldn’t have batted an eyelid over ‘shit’ or ‘piss’ as those words were commonplace 500 years ago. And the c-bomb was famously and publicly included in street names all over England between 1230 and 1561AD. In many European languages, the word for “bear” was taboo simply because it was a big scary animal that ate people. Back then, “by God’s nails” was the most shocking expletive and would have seen the utterer completely “sarded” or “swived” – both ancient words that mean the same as today’s “fucked.”

In 2015, three Australian protestors had charges of ‘offensive language’ dropped after they’d been arrested for shouting “Fuck Fred Nile” over a megaphone in public. The judge ruled “fuck” to be a part of everyday Aussie vernacular, citing the inoffensive usage in “you fucking beauty!”

Thus is the constant evolution of language.

However, swearing is still blacklisted from advertising. The Advertising Standards Board’s (ASB) code of ethics includes Section 2.5 Language, which provides guidelines on obscene terms and obscured obscenities. The Board, now known as Ad Standards, conducts rulings on consumer complaints. The ASB website puts all the cases into public domain – some very interesting reading – to show how they determine if an ad gets banned. Or not.

Over the years, advertisers and agencies have had a fucking good crack at getting swear words into ads. It’s a gamble to outright drop a swear into a commercial, even if you think society has evolved so the offending word is no longer offensive. After creating this controversial but charmingly on-brief ad in 2003, Volkswagen had a change of heart and ran it online rather than on-air, citing “budget cuts”.

If writing a swear word into a script isn’t possible, here are a few ways potty-mouthed creatives have tried to give their client’s ads that special oomph that only a swear word can muster.

METHOD 1: THE FORKING SWITCH

One of the primary methods is to replace the swear word with an innocuous word that sounds similar. Most famous was Kmart’s “Ship My Pants” in the US, which didn’t air on TV but was used as online content.

Back in 1999, a very young Rich Hall faux-swore in a hilarious but odd commercial for Miller beer.

Homegrown examples of faux profanity include YouFoodz’s 2017 TVC ‘Un-forking-believable’ that featured a kid doing a Gordon Ramsey impersonation with a fork.

The ASB banned the YouFoodz ad. However, according to case report 0423/17, the Board considered the ad made it obvious the kid wasn’t actually swearing but found the ad to be in breach because it was a child pretending to swear. The ad was banned but reappeared with beeps over the non-swearing. Unfortunately, it still drew complaints and the ASB determined it was still in breach, possibly more so, because now the kid appeared to be genuinely swearing instead of pretending.

By comparison, Handee Ultra got away with it when their ad drew consumer complaints but case report 0291/15 found uttering the word “sheeeeet” when you spill something and grab a sheet of Handee Ultra to wipe it up was OK because “the word is contextualised immediately by onscreen imagery of the product being used”.

While KFC recently created a TVC in which a kid replaces “Fuck it!” with “Bucket!”, they weren’t the first. Ten years ago Air Asia ran a billboard using a similar faux-swear that received a complaint but was approved to stay.

METHOD 2: BRAND BOLLOCKS

The second method for sneaking in a swear word is to use the brand name itself. This doesn’t work for all brands, but has proven to be effective at dodging ASB bullets.

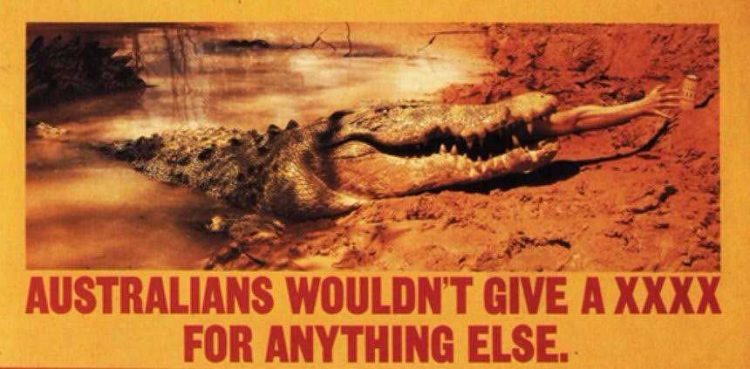

Decades ago, the sunshine state’s own beer brand XXXX made great use of their apparently censored name to imitate a censored swear word.

A personal favourite is BCF, the boating, camping and fishing retailer who wants us to have BCFing fun. This light-hearted and strategically insightful ad received a few complaints but the ABS dismissed them, determining that while ‘effing’ in isolation would be a breach, the ad by virtue of the jaunty jingle and the graphics clearly explained that F is for fishing. A case of profanity being in the viewer’s ear, rather than the speaker’s mouth.

The brand that took this to a new level was French Connection in 1991 when founder Stephen Marks and ad legend Trevor Beattie saw the opportunity for a massive rebrand on the fax header from FC’s Honk Kong office that read “From FCHK to FCUK”. The controversial but pivotally successful initialism lasted for 14 years worldwide, yet has remained in the consumer vernacular.

METHOD 3: F*** YOURSELF

The third way to include profanity in an ad without actually including it is by self-imposed censorship: replacing the taboo word with another sound like a beep or a safe word. (My safe word is “pie” – because getting someone to stop should be easy as.)

IKEA won a silver Siren award for a radio ad about their kitchen product, which includes 6 beeps over a young boy’s show and tell. Surprisingly, there appears to have been no complaints against this ad so one can assume it flew under the radar in terms of media coverage.

The key to obscuring a word is the context that it’s used. It can’t be used in animosity or nastiness, and should be used in a manner consistent with colloquial use such as venting frustration rather than randomly included for shock or salaciousness.

In the UK, Burger King combined methods two and three to use its brand name as the visible part of the self-censored taboo word.

METHOD 4: FRAK IT

There is a space between what is a taboo word and what sounds like a taboo word. To be truly identified as a swear word, the word must be formally defined (by Oxford, Collins, et al). Otherwise, it’s just a random sound dropped into dialogue at the right contextual moment.

While this method has been employed by TV and film writers to avoid censorship and given us such gems as frak, smeg, frell, zarking fardwarks, yarblockos, jagweed, cloff-pronker and Ross Geller’s double fist bump, it has rarely been used in advertising. The trick is creating a word that sounds like an expletive but isn’t, and using it without aggressive context that could deem your ad a zarking breach by ASB guidelines.

So, why, with many rules governing taboo words, a segment of indignant and outspoken consumers, and the risk of having an ad banned, do we want to swear in ads?

We do it because these words have an important and distinctive effect. They convey human traits and contextual communicative elements that no other words can. They give impact. They can add authenticity to a moment and improve relevance to certain audiences.

A study from Keele University in Staffordshire proved that swearing alleviates pain. In fact, students were able to keep their hands in ice water for 50 per cent longer when they swore. Cognitive scientist Benjamin K. Bergen discovered that responsive expletives originate in a completely different part of the brain than the rest of our language. Swear words live in the animal part of our brain that developed earlier in our history and was once used for grunting, howling and screaming.

When we swear, we’re using raw emotion.

Research from Stanford, Cambridge, Honk Kong University, and Maastricht University found that those who swear are more likely to be honest and perceived as trustworthy because profanity is less deceptive and unfiltered. Behavioral research at the University of Rochester discovered a strong link between swearing and intelligence. Psychologists at the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts conducted several experiments that showed people who swear have greater vocabularies. And a study from the University of East Anglia found that swearing promotes better teamwork in an office environment.

In conclusion, if you swear, you’re more emotional, intelligent, trustworthy and better spoken as well being a team player and with a higher pain threshold. Fuck yeah. As a brand, swearing in advertising could show you’re more emotional, authentic, and honest.

And for the record, I promised my daughter she will be allowed to add one swear word to her vocabulary each year from the age of 10, but only if she uses them fucking appropriately.

Notes: I opted to exclude the well-known “C U in the NT” tourism campaign because it wasn’t a client-authorised campaign. I also excluded AAMI’s “Woop Woop (Up Ship Creek)” ad because the US Kmart ad used the ship/shit switch four years earlier and to greater effect. For other potty-mouthed advertising, see Orbit’s “Clean Feeling” ad, Irn-Bru’s “Don’t be a Can’t” campaign, KFC’s “FCK” apology print ad, and Virgin’s “Don’t give a shiatsu” billboard.

Latest News

Sydney Comedy Festival: Taking The City & Social Media By Storm

Sydney Comedy Festival 2024 is live and ready to rumble, showing the best of international and homegrown talent at a host of venues around town. As usual, it’s hot on the heels of its big sister, the giant that is the Melbourne International Comedy Festival, picking up some acts as they continue on their own […]

Global Marketers Descend For AANA’s RESET For Growth

The Australian Association of National Advertisers (AANA) has announced the final epic lineup of local and global marketing powerhouses for RESET for Growth 2024. Lead image: Josh Faulks, chief executive officer, AANA Back in 2000, a woman with no business experience opened her first juice bar in Adelaide. The idea was brilliantly simple: make healthy […]

Is Meta’s New AI Chatbot Too Left-Wing?

Meta's chatbot accused of being left-wing after being caught wearing a Che Guevara T-shirt & listening to Billy Bragg.

TV Ratings (23/04/2024): Why Did No One Tell Angela That Farmer Wants A Wife Is Set On A Farm?

As wonderful as this headline is, let's face it, we all know an 'Angela', don't we?

PubMatic Unveils New AI Partnership To Turn Social Posts Into Ads For Any Digital Channel

Here's some nifty tech for turning social posts into ads. Assuming said posts aren't one-star character assassinations.

Intuit Mailchimp Makes A Splash With Its First Australian Brand Campaign

Ever laugh along at a gag you didn't get so as not to appear dumb? Get ready for more feigning with this new work.

GumGum’s Rob Hall: Advertisers Can No Longer “Rely On Binary Descriptions” Of Consumers

If anyone's got their finger on adtech's pulse, it's Rob Hall. He also avoids using the good paper in the office printer

Mastercard Nabs Florencia Aimo From Marriott International

Marriott International's Florencia Aimo jumps from the hotel business to the exploitative credit card one.

Bastion Agency Appoints Cheuk Chiang As New ANZ CEO

Cheuk Chiang takes the reins over at Bastion Agency. But not the rains down in Africa.

Spotlight On Sponsors: Major Sponsorship Wins After A Disappointing Week In Sport

B&T continuing our deep dive into local sport sponsorships & that's despite not a single offer of a free ticket as yet.

Macca’s Marketing Director, Samantha McLeod On Big Mac Chant: “What Was Once Old Is Now Cool Again”

Macca's using the power of nostalgia in latest Big Mac campaign. Well, only for those who've ever eaten one sober.

World Premiere Of Midnight Oil: The Hardest Line To Open Sydney Film Festival 2024

Oil's biopic to open Sydney Film Festival. Here's hoping Molly Meldrum will take his pants down at the premiere.

Entries Are Now Open For The 2024 Brandies, IntelligenceBank’s Annual Brand Marketing Awards

The Brandies are, of course, a prestigious marketing gong and not the mystery tipple favoured by nannas everywhere.

The Fred Hollows Foundation Appoints Ardent For PR

Yes, we all like to have a joke at PR's expense. But sometimes it does important work, like this.

AI, eCommerce & Marketing Specialists Are In Increased Demand By Businesses, New Data From Fiverr Shows

Has your philosophy & anthropology degree left you with nothing but a huge HECS debt? Here's what you should've studied.

Perth’s First 3D Anamorphic Billboard Arrives Courtesy Of oOh!media

Do you love a buzzword? Now you can add anamorphic to the list as it relates to billboards, not a colleague's ears.

MasterChef Australia & Crown Resorts Launch Unique Dining Experience With ALUMNI

A pop-up restaurant staffed by MasterChef contestants! That's fine dining prices for first-year apprentice chef cuisine!

Amanda Laing Announces Resignation From Foxtel Group

Foxtel's chief commercial & content officer heads for the exits. Read nice things the bosses said about her right here.

The Lost Letters From Our Diggers: News Corp Unveils ANZAC Day Special

It's nice when brands respectfully acknowledge ANZAC Day.

Howatson+Company Acquires Akkomplice

Large indie acquires a slightly smaller indie. Much like a shark eating a tuna, just with less thrashing and blood.

Google Delays Third-Party Cookie Deprecation Again

In good news for the sale of picture library biscuit photos, Google continues to tease over the end of cookies.

Education A Low Priority For Aussies More Concerned With Cost Of Living Forethought Study Reveals

Study finds Aussies cutting back on education due to cost of living. Booze & Uber Eats sales remain largely unaffected.

“I’m Still The Same Person That I Was”: Rikki Stern Says “Fucc It” To Cancer Stereotypes

B&T always happy to promote the anti-cancer cause. Even brands that massively overdo it with the hot pink.

The Unapproved Climate Certification Allegedly Causing Mass Greenwashing

Are you left flummoxed in the canned tuna & free range eggs aisle? Just wait till this green certification gets up.

TV Ratings (22/04/2024): Fans Mock “Over The Top” Reaction To New MasterChef Judges

MasterChef returns for its 2024 season. B&T stands by putting peppercorns in Gravox & no one will be any the wiser.

Dentsu Restructure: Muddle, Harvey & Johnston Take Leadership Baton As Bass & Yurisich Exit

A large broom has swept through Dentsu's local ops this morning, taking with it some big names & the air con's cobwebs.

Industry Shares Trends Shaping The Industry This International Creators Day

B&T's asking adland creators to reveal their top trends. And it's not good news for your Jenny Kee cardigan collection.

Mable Extends HOYTS Sensory Screenings Partnership

Mable has extended its HOYTS sensory screening partnership. Vigorously defends its two-star Oppenheimer review.

Orphan Launches ‘They Need Our Help. We Need Yours’ For Children’s Cancer Institute

Anything to do with childhood cancers has B&T's 110% support. That said, we do ignore the red meat & alcohol warnings.

Smile Team Orthodontics & Keep Left Collaborate On Smile-Inducing Campaign

As parents would attest, given the cost of orthodontics you'd expect this campaign to be a lavish production indeed.

Opinion: How Video Calls Neglect Learning Diversity

Need an excuse to duck out of a video call this arvo? Show this to your boss.

DoubleVerify Achieves First-Of-Its-Kind Responsible AI Certification From TrustArc

DoubleVerify receives responsible AI certification. However, not its robotic vacuum that's been seen menacing the cat.

Smile For A Good Cause: The Social Media Campaign Giving Back To The Community

Are you known as the office Austin Powers? More for you teeth than shagability? Get snappy new fangs with this news.

Elon Musk Mocks Albo After ESafety Wins Court Injunction Against X

Albo's 2024 from hell continues - Rabbitohs in crisis, down in the polls and now feuding with world's richest man.

Real Estate Developer In Hot Water Over “Sexually Exploitative” OOH Campaign

Real estate agents again tops in the 'least trusted profession' polls, nudging used car salesmen & ad creatives.

Epsilon’s Shane Hanby: Post-Cookie Era Relies On “Teamwork” Between Brands, Marketers & Tech

This pro predicts more "teamwork" in a post-cookie era. Which spells bad news for the uncooperative or plain stubborn.